Context Matters

News coverage of a recent ICE raid at an Omaha meatpacking plant exemplifies how both Reds & Blues selectively erase pivotal facts from their narratives

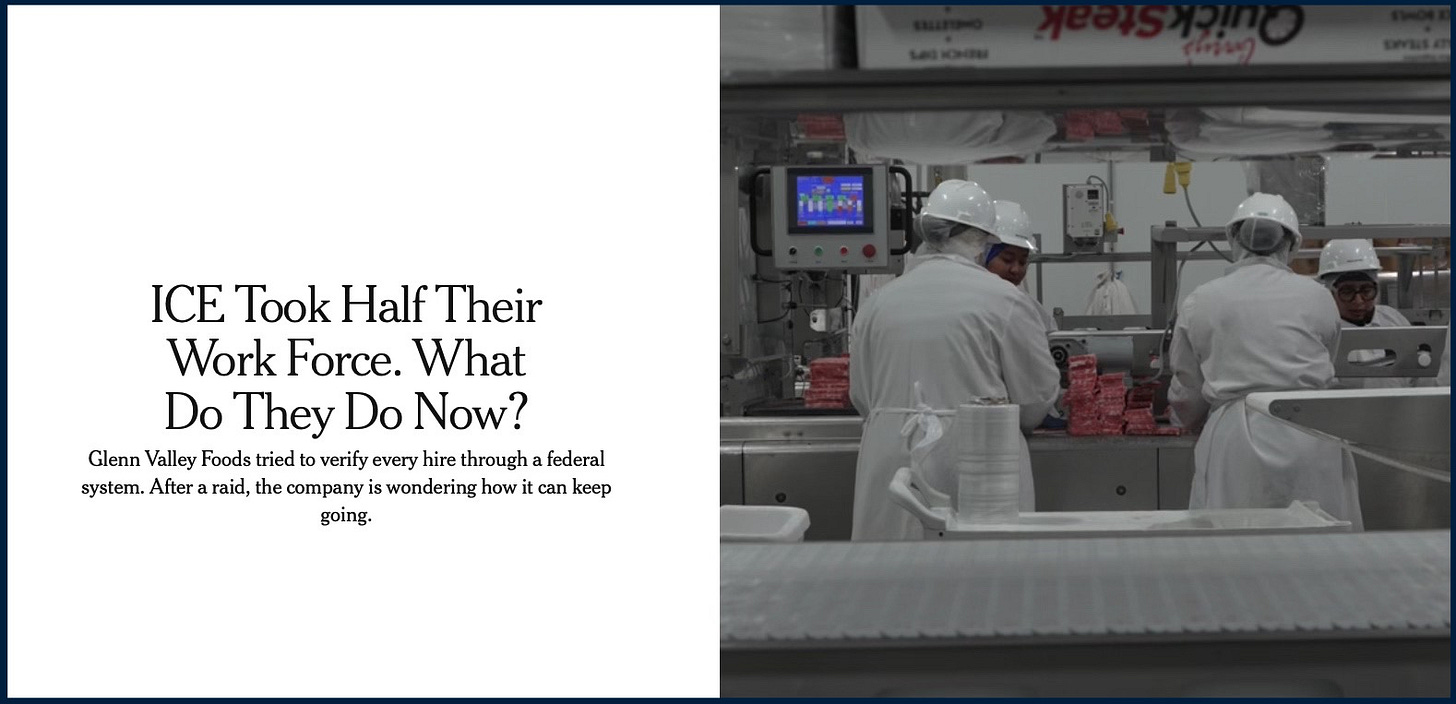

Scanning last Sunday’s New York Times headlines, I was drawn to their “Great Read” feature on a recent ICE raid at an Omaha meatpacking plant. I’d already followed this story a bit, as I found it disturbing. So I was interested to see what the NYTs take on this now over six-weeks old story (which, oddly, they hadn’t covered before) would be.

Basically, what happened was that at least 76 workers at Glenn Valley Foods, a meatpacking plant in Omaha, Nebraska, were arrested by ICE on June 10th. According to NBC News (which, unlike the NYTs, reported on it promptly) all were valued employees. Many had been working there over 15 years. None had prior criminal charges or convictions. And at least according to NBC, no new ones had been filed.

Nonetheless, about a dozen of those arrested were deported or transferred to a detention center out of state. At least 63 were placed in the nearby Lincoln County Detention Center. None of this had been welcomed by local officials. County Sheriff Jerome Kramer told reporters that he planned to help the detainees “complete the process to correct their work status and reunite them with families or employers.” His sympathetic posture seems understandable, as hard working, law abiding, and closely knit families had been torn apart by the raid. It took the four kids of one middle-aged Mom who’d been arrested, for example, three days simply to figure out where she’d been placed.

To put my cards on the table, I fully support the Trump Administration’s commitment to securing U.S. borders and deporting migrant criminals. I don’t feel the same way at all, however, about arresting, incarcerating, and/or deporting illegal immigrants who are (other than their residency status) law abiding and hard working, usually at very low-wage, unpleasant, and often dangerous jobs. This is particularly true if they have families and have lived in the U.S. for well over a decade. While I’m not sure exactly what the right policy would be, I think that’s absolutely a discussion worth having. A more differentiated — and humane — system could and should be developed.

That said, political narratives these days are never what they seem. Doing a little more research on this story, I quickly found out that Fox News had (unsurprisingly) covered the Omaha raid quite differently than NBC. “ICE has uncovered a massive identity theft scheme led by illegal immigrants and possibly tied to organized criminal networks following a workplace raid at a meatpacking plant in Omaha,” the Fox story began. Reportedly, those arrested had been “using stolen Social Security numbers and identities to unlawfully obtain employment authorization, wages and benefits at the expense of over 100 victims,” many of whom had experienced “‘devastating financial, emotional and legal consequences as a result of the identity theft.”

As anyone who’s ever had to deal with identity theft knows, it can be a very serious problem. Examples cited in the Fox News report included one full-time nursing student who lost her college tuition assistance because of fraudulent reports that she’d earned too much money, a disabled worker who was unable to access his Social Security disability payments due to identity theft, and a California resident who’d spent almost 15 years trying to secure her identity and fix the financial damage done by the fraud.

Again unsurprisingly, not a word of this was alluded to in The New York Times coverage over a month later. Instead, that story decried what was portrayed as the perverse economic outcomes of the ICE raid for all involved — not only the workers themselves, but also their employer, community, and the state of Nebraska, along with the meatpacking industry, the supply chains that equip it, and the consumers who will allegedly have to pay higher prices for beef. The Times presented a poignant tale not simply of needless human suffering, but also of heedless economic destruction that would ultimately impact countless Americans quite badly.

“For more than a decade,” it began, “Glenn Valley’s production reports had told a story of steady ascendance — new hires, new manufacturing lines, new sales records for one of the fastest-growing meatpacking companies in the Midwest. But, in a matter of weeks,” it continued, “production had plummeted by almost 70 percent” due to the ICE raid. “‘It’s terrible for everyone,’” HR Director Alfredo Moreno told reporters. “‘I’ve seen whole companies go under after a raid. The supply chain stalls. Beef prices go up. Consumers pay more.’” Company president Chad Hartmann confirmed this dire prediction: “‘The ripple effects,’ he said, nodding.”

Meanwhile, the Times noted, children of arrested workers “were struggling at home and in some cases subsisting on donations of the company’s frozen steak.” In other words, Glenn Valley Foods was a beneficent employer that cared about its employees and was doing its best to help. This may well be true. Still, the following paragraph jumped out at me as obviously over-the-top:

Glenn Valley paid well, with an average hourly wage of almost $20 and regular bonuses, but the work was repetitive and demanding. Employees who came mostly from Mexico and Central America stood on a manufacturing line for as much as 10 hours a day, six days a week, and processed hundreds of pounds of meat through dangerous machinery in a cold factory.

Responding to criticisms that his plant’s hiring of illegal immigrants was “‘stealing American jobs,’” Glenn Valley Foods owner Gary Rohwer explained that “‘there are some jobs Americans don’t want to do.’”

One question the New York Times reporters didn’t ask, however, is why. Might it have something to do with the fact that the average wage at Glenn Valley Foods is under $20 an hour (with no benefits mentioned) and that the average work week is 60 hours in uncomfortable, unhealthy, and dangerous conditions? And could it also be the case that many American workers still have some lingering sense of a time in which the average American meatpacking plant worker earned twice as much while working half as many hours?

The answer is obvious. Unfortunately, however, very few of our elite journalists, academics, politicians, and policy makers are asking, let alone answering such questions. And the “Great Reads” feature in our most prestigious paper of record isn't encouraging them or anyone else to do so — in fact, quite the contrary.

What the American Worker Lost

The story of the American meatpacking industry is emblematic of many other sectors and industries. To compare apples to apples, however, let’s take a brief look at the job profile of the average American meatpacking plant worker during the mid-1960s:

The average hourly wage (including benefits) for a unionized worker was $39.12 in 2025 dollars.

Typical benefits included 1) employer-funded health insurance plans with low co-pays, 2) defined-benefit pension plans based on years of service; 3) 1–3 weeks of vacation based on seniority and 8–10 paid holidays annually, and 4) supplementary benefits such as life insurance and compensation for layoffs.

The standard workweek was 40 hours, which set by union contracts and aligned with Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) norms.

Most workers averaged about 42 hours, but were paid two hours overtime at a mandated rate of 1.5x pay.

About 95% of meatpacking workers outside the South (which had lower unionization rates) belonged to a union. Even when the South was included, however, the national unionization rate was still in the 80-90% range.

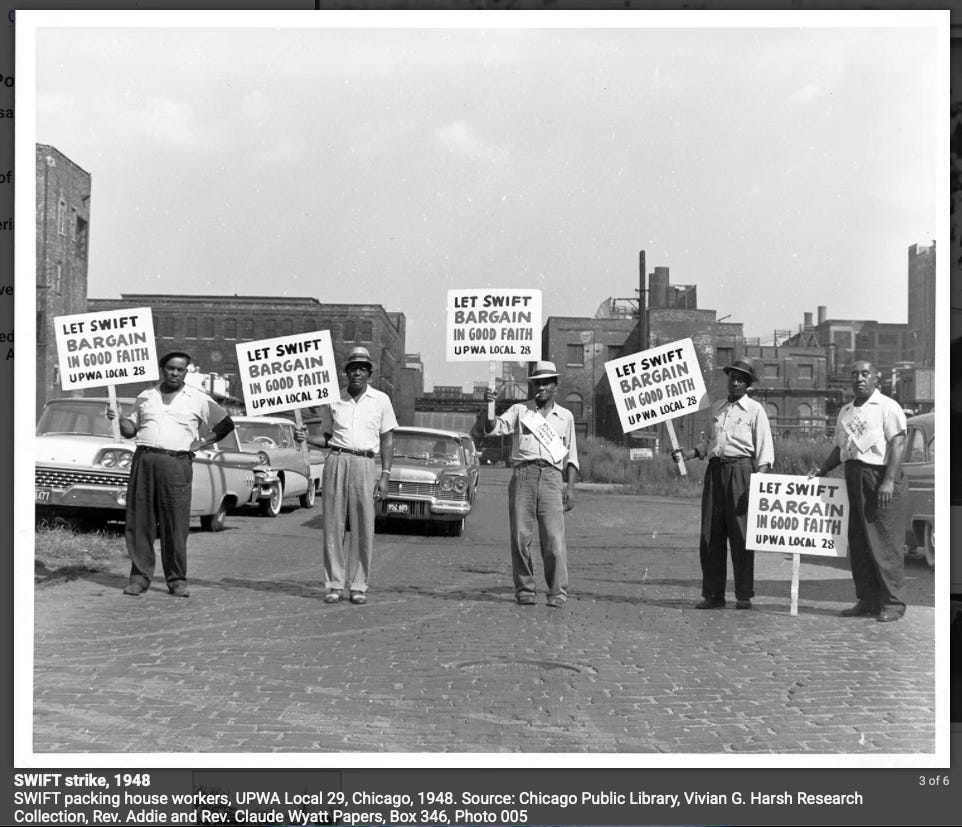

At the same time, the now widespread assumption that New Deal labor laws and the subsequent growth of American unions during the 1930-60s only helped white native-born workers is simply not true. On the contrary, the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) prioritized organizing across racial and ethnic lines. The meatpacking industry employed significant numbers of African American, Mexican American, and other immigrant workers, particularly in urban centers like Chicago, Kansas City, and (then as now) Omaha.

In fact, one of the UPWA’s official slogans was “Negro and White, Unite and Fight!”

By the mid-1950s, about 25-30% of the UPWA's membership was Black. Mexican Americans and other immigrant groups were also well-represented, especially in the Midwest and Southwest. The UPWA made a point of promoting non-white and immigrant workers into leadership roles and actively supported the inclusion of women and minorities in its ranks. They were also strongly aligned with the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s-60s: They contributed to leading activists organizations such as the NAACP and the SCLC, and participated in civil rights campaigns including the 1963 March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Fast forward to the present, and the job profile of the average American meatpacking worker looks quite different:

The average hourly wage (including benefits) is now $19.50 an hour, literally half of what workers were earning 60 years ago.

82% of the workforce is non-unionized.

Only about 50% of these non-unionized workers have health coverage. And it’s worse than it used to be, typically with high deductibles and sizable employee contribution rates.

There is less paid time off (1-2 weeks vacation, 5–8 holidays, and minimal or no sick leave).

There are no pensions or supplemental benefits.

From the Times report, it would seem that the length of the workweek is not regulated and there is no overtime: Workers were reported as regularly putting in 60 hours a week, which is 50% more than they were 60 years ago.

Why the change? According to a 2010 article in Dissent:

In the late twentieth century the meatpacking industry restructured and moved out of cities like Chicago and Kansas City. Corporations wanted to escape urban environments with powerful unions . . . The labor force composition also changed, as companies began energetically recruiting Mexican workers.

. . . The restructuring of the meatpacking industry also generated lower wage structures; deskilling; much faster production line speeds; and, not surprisingly, much higher rates of injury.

Notably, the article goes on to explain that “the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 required that Mexico eliminate both tariffs that protected corn farmers as well as a measure in its constitution forbidding the sale of communal peasant lands.” The consequence was “the loss of at least 1.5 million agricultural jobs in Mexico.” This displacement of peasant farmers produced an influx of illegal immigrants seeking work in the U.S. — which, in turn, created an easily exploitable labor force. Consequently, the good unionized jobs that had once been the standard for American workers were gutted.

Undocumented workers now constitute 25-50% of the workforce. Blaming these illegal immigrants for the loss of good American working class jobs, however, is not only unfair, but historically inaccurate. NAFTA (which, it must be remembered, was passed under the Clinton Administration) paved the way. And the most powerful companies in the industry exploited the opening it created by sabotaging unions and recruiting illegal immigrant labor.

The results were obscenely profitable: The CEO-to-worker pay gap in the U.S. meatpacking industry is estimated to have widened from 21:1 in 1965 to 344:1 in 2022. As in other sectors, CEO compensation grew massively thanks to stock-based compensation and industry consolidation: In 2017, for example, Wan Long, Chairman and CEO of WH Group, the parent company of Smithfield Foods, earned $291 million. At the same time, corporate profit margins increased significantly: In 2021, Tyson Foods reported a net income of $3 billion and JBS reported $3.047 billion.

Such numbers belie the belief that U.S. companies couldn’t afford to keep paying workers the wages and benefits they received back in the mid-1960s. True, American corporations had to adjust as other countries industrialized and became more competitive. True, they were often over-regulated, and that needed to change. Nonetheless, this shift towards a stunningly more unequal society was not the inevitable outcome of ironclad economic laws and market forces. On the contrary, it was driven by policy choices that both Republicans and Democrats supported (e.g., NAFTA) and profit-maximization strategies that many corporations deliberately and aggressively pursued.

Erasing History

The story of how the UPWA organized to make tremendous gains for ordinary Americans of all races, ethnicities, and genders is only one of many examples of how America’s true social justice history has been lost. Of course, the history of the American labor movement contains plenty of egregious examples of racial, ethic, gender discrimination as well. Many unions not only attempted to organize across racial and ethnic lines as far back as the history goes, however — they also often succeeded. And in cases like the UPWA, that success translated into concrete gains that enabled ordinary people to earn a good living, have families, build communities, and contribute to a common American democratic project dedicated to equal dignity, respect, and opportunity for all.

Thanks to the rise of the woke “left,” however, today’s progressives have brainwashed themselves into believing that the U.S. has always been and will forever be nothing more than an irredeemably oppressive country mired in white supremacy, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and the like. They defend open borders and unchecked illegal immigration as a self-evidently righteous cause, oblivious to the fact that recruiting easily exploitable labor has been part of a neoliberal agenda that brutally dismantled the hard-won gains of the American working class. Rather than grappling with this history and thinking into how to rectify it, today’s progressives simply write off the working class as white racists — which is ridiculous demographically (as the working class is obviously not all white) and offensive culturally (as the white working class is no more racist than white progressives, and arguably much less so).

Of course, this makes it easy for the Trump Administration to position itself as the sole defender of the working class — and their promise of “mass deportations” is a central part of that. Combined with the reshoring of American manufacturing and leveraging of foreign direct investment to build new plants and create new jobs in the U.S., the working assumption is that the resultant tight labor market will naturally improve wage rates and working conditions, as employers will need to do more to compete for workers. And there is definitely a logic to this as far as it goes.

History indicates, however, that it will take far more than market forces to reestablish good working class jobs. And while pro-union conservatives like Oren Cass are developing a policy agenda to push the Republicans in that direction, the likelihood that the GOP will adopt and implement it strikes me as low. Alternately, the danger of scapegoating illegal immigrants for problems that were in fact caused by much bigger and more powerful forces strikes me as all too high.

It’s depressing to know American history enough to have a sense of just how much the average American has lost during the past 60 years. At the same time, however, recovering the lost history of how ordinary people organized across formidable lines of social difference to achieve concrete gains is inspiring. This is particularly true when it’s connected to a larger story of how Americans have worked collectively to achieve a vision of old-fashioned social justice. That democratic imaginary is a central part of the American legacy. But it’s been mostly erased from our collective memory. Recovering, reimagining, and renewing it will be difficult. But it’s work that can and should still be done.

You can't live in the shadows without engaging in some sort of ancillary crimes, be it identity theft of facilitating your company underfunding social security by not paying payroll taxes on its illegal workers. The reason the story is so sad is because these folks were allowed to live in the shadows a long time, without any path to legal citizenship, and now they have been discovered.

Great piece and good to hear from you again!