Liberalism & the Left/Right Horseshoe

Political heterodoxy & creative freedom in the ruins of (neo)liberalism

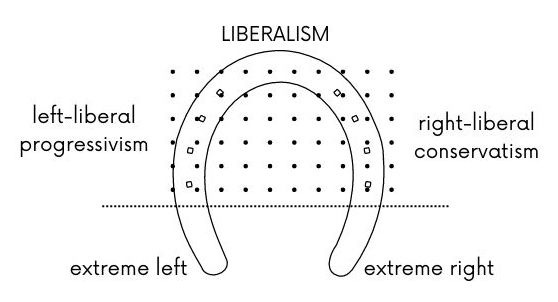

Have you heard of the "horseshoe theory” of politics? Basically, it’s the idea that at the extremes, the politics of the far left and the far right start to converge, just like the ends of a horseshoe. Mostly, what makes this concept useful is that it challenges the more standard idea that the political right and left anchor opposite ends of a linear spectrum:

Until recently, a certain version of horseshoe theory was tacitly assumed in the U.S. and other liberal democracies. True, most people didn’t consciously frame their thinking in those terms. Still, there was a foundational, taken-for-granted assumption that liberalism — broadly defined as a political tradition rooted in a commitment to individual rights and liberties, a market-based economy, limited government, and the rule of law — dominated most of the top of the horseshoe. The bottom, in contrast, was understood to converge towards totalitarian communism on the left (Stalinism, Maoism, etc.) and authoritarian fascism on the right (e.g., Nazism, Francoism).

Graphically, the “old” (mid-1940s to mid-2010s) liberalism-dominated horseshoe looked something like this:

In the U.S., the top portion was divided between progressives (or simply “liberals,” which inevitably makes this nomenclature a bit confusing) and conservatives. By and large, left-liberals advocated for government action to promote greater social equality — more civil rights laws, social welfare protections, public regulation of private business, and so on. In keeping with the traditional tenets of liberalism, however, this was understood not as an end in itself, but rather as a means of supporting the principle of equal rights and opportunities for all.

Right-liberals, in contrast, advocated limiting the size and power of government — particularly the federal government, which is most distant from local (small-”d”) democratic control — as much as possible. Opposed to the reforms of the New Deal from the get-go, they pushed for the return of a more “classical” form of laissez-faire liberalism. With a few exceptions (e.g., national defense), the combination of individual initiative, the free market, and voluntary associations was seen as the proper driver of a healthy, free society — as opposed to what was seen as almost inevitably inept, wasteful, and coercive top-down government control.

The more that it was assumed that such basic conflicts of goals and visions would play out within a commonly shared liberal framework, the easier it was to see the ensuing process of conflict and compromise as part of a healthy democracy. After all, a whole range of critical social, economic, or legal issues inevitably involves trade-offs between core liberal principles of liberty and equality. And there’s no such thing as a perfect balance: Different individuals have different priorities, different groups have different needs, different organizations face different exigences — and so on. Not to mention, the world is constantly changing.

So, in a liberal democratic society, the best way to hammer out law and policy is through a structured process that includes a wide range of competing interests and groups. Or so, at least, the dominant liberal storyline went until Trump’s 2016 victory upended this once largely taken-for-granted conceptual framework entirely, sending the U.S. into a vertiginous tailspin that continues to this day.

Fragmentation & Conflict

Suddenly, it became evident that this way of thinking about American politics was no longer comprehensible, let alone compelling for a decisive percentage of the population. Long-simmering internal contradictions within the dominant progressive and conservative coalitions — which had never been as coherent or unified as they pretended to be — burst out into the open. At the same time, a variety of alternative political ideologies emerged and/or grew more powerful, creating new fractures, divisions, and alternatives that would have been unimaginable earlier.

On the right, the Trumpers denounced NeverTrumpers as RINOS (Republicans In Name Only) or worse. The latter returned the favor by joining progressives in denouncing Trump and his MAGA minions as a racist threat to democracy. Meanwhile, libertarian conservatives disdained both the establishment GOP and the MAGA upstarts. Then, to make everything even more confusing, a diverse and in some cases logically conflicting variety of “new right” factions became newly vocal and visible. What, for example, do buttoned-up Catholic integralists have to do with gleefully nihilistic shitposters? Nothing, really, except that they’re both “on the right.”

Meanwhile, on the left, the wokesters (who I’m now thinking of as “post-liberal progressives,” more on that in a forthcoming post) suddenly seized a whole lot more power. Newly established social media capabilities were ruthlessly leveraged to recruit, discipline, and control followers, while at the same time scaring doubters, resisters, and critics who otherwise considered themselves “on the left” into silence, submission, and/or ostrich-like denial. As the corporate media ran countless articles claiming that “cancel culture” didn’t really exist, woke crusades against targeted individuals charged with racism, sexism, transphobia, and/or “sexual misconduct” churned relentlessly yet capriciously on. Not surprisingly, left-of-center politics consequently developed a deep split between those who criticized and rejected woke politics and those who did not.

Meanwhile, Bernie Sanders’ campaign to build a new democratic socialist movement (which, despite this branding, was really more of an attempt to revive the now-defunct tradition of New Deal liberalism than anything else) and win the Presidency foundered — twice. Hit by corporatist establishment Democrats from the right and woke social justice warriors from the left, the challenge of winning over a voting public that, by and large, either doesn’t speak or passionately rejects the language of “socialism” (excepting those who are in a niche subculture and, most likely, college-educated and under 30) was insurmountable. Consequently, what remained of the non-woke social democratic left became even more marginal (although a few stalwarts maintain a terrific online presence, like Jen Pan and Briahna Joy Gray).

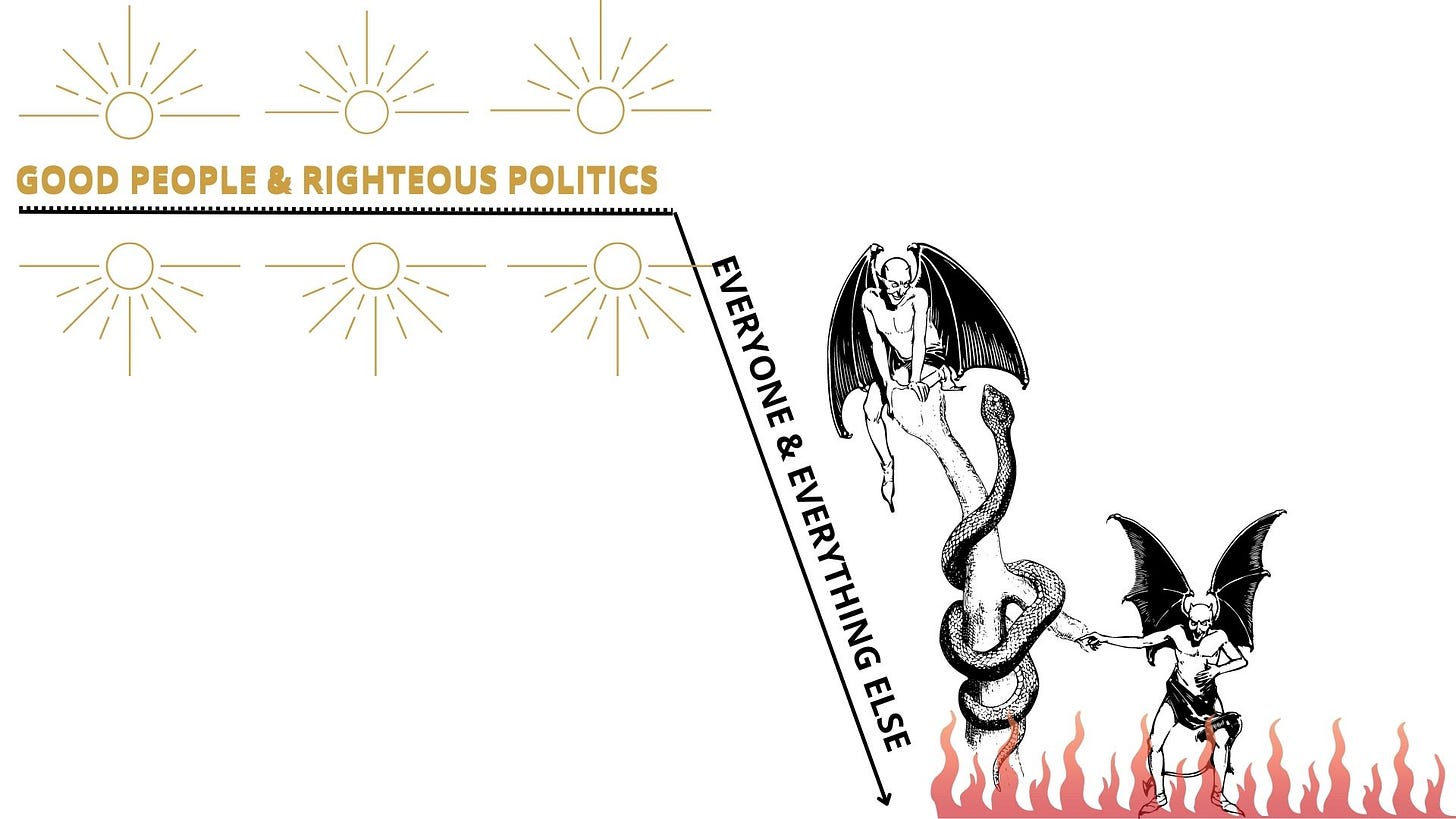

Despite such political fragmentation and churn on both the right and the left, the two major parties, along with their accompanying media apparatuses, have nonetheless managed to dominate political discourse with a good-guys-versus-bad-guys narrative that obscures everything else. Rather than grappling with the true diversity of political thought that exists today, we’re relentlessly bombarded with the message that there are only two teams and we must choose one. After all, The Good People are fighting valiantly to “Save Democracy” — or, as the case may be, “Make America Great Again” — while The Bad People are on the brink of destroying everything that makes life liveable, let alone worthwhile.

Faced with such a crisis, who are you to sit on the sidelines? You must choose a side! And there are two and only two options! Anything else is really just a gateway drug that will fast-track you down the slippery slope to perdition. Or so, at least, “they” would have us believe.

Graphically, the reigning political narrative on both the right and the left now looks something like this:

. . . Right? Whether it’s the righteous forces of MAGA fighting against the blue-haired Marxists, baby killers, and “groomers,” or the True Blue Democrats fighting against Trumpist fascism, racism, misogyny, and transphobia, that pretty much sums it up. It would be laughable were it not so dangerous.

Neoliberalism & Narrative Control

How did we get here? Although Trump-hating “resistance liberals” like to think that everything bad that’s ever happened can be 100% blamed on the GOP (while right-wingers, of course, assume the opposite), the real story is more complicated. Of course, it’s hard to think into such complexities when the political heat is always turned up to the boiling point and there’s always a make-or-break crisis. Plus, even the most well-informed scholars inevitably disagree on such issues. But that’s as it should be — after all, today’s society really is mind-bogglingly complex. Anyone who insists that there’s only one self-evidently correct answer to any big social question is either delusional or lying.

That said, some analyses are infinitely better than others. And so, caveats aside, my best take at the moment is that the following macro-historical trends were key in creating the conditions in which today’s toxic mess developed:

The replacement of the postwar liberal model that dominated the 1940s-70s with “free market”-based globalist neoliberalism.

The strong support for this neoliberal turn by both the Republican and Democratic party establishments.

The concomitant shift from a manufacturing-based economy to one driven by high finance and big tech.

The corresponding growth in socioeconomic inequality and erosion of the working-to-middle classes.

The growth of mass incarceration as the primary means of controlling hyper-marginalized low-income populations (disproportionately but by no means exclusively Black) whose labor was no longer needed in the new post-industrial economy.

The Democratic Party’s shift away from the working and middle classes and towards the college-educated elite.

The institutionalization of the right and left flanks of the “culture war” centered on issues of race, gender, and sexuality in politically siloed media, nonprofit, and interest/activist group ecosystems.

The exponential growth of the military-industrial complex and surveillance state, particularly in the wake of 9/11.

The hardening of politically salient “Red vs. Blue” geographic divisions, including but not limited to gerrymandered electoral districts that ensure one-party rule.

Obviously, these factors are entwined in complex ways. And there are others to consider besides. Regardless, the basic point is that many, if not most of these trends date back to the 1970s-80s. The grounds of politics, economics, technology, culture, and society have been shifting for decades. Many of us simply had no sense of just how much these changes were undermining the “old” liberal order until the earthquake that was President Donald Trump erupted and blew any remaining delusions of stable continuity to bits in 2016.

Unfortunately, the mendacity of our dominant political discourse means that we’re relentlessly discouraged from considering, let alone seeing this sort of bigger picture even now. True, there are endless intelligent takes and good resources out there. I could (and sometimes do) spend all day reading interesting articles and listening to good podcasts downloaded off the Internet. The problem isn’t a lack of information. Rather, it’s who has the megaphone. When Team Red and Team Blue are constantly blaring at each other at top volume, smaller voices are easily drowned out (or, as the case may be, shut down as “misformation”).

There’s a determined effort to control the narrative. And to a dismaying extent, it’s working. Far too many people continue to take what they’re being told on NPR — or, on the opposite side, Fox — as gospel. Social media algorithms keep us in our information siloes. Google rigs our search results. The Director of the Biden Administration’s new “Disinformation Governance Board” (housed in the similarly Orwellian-sounding Department of Homeland Security) even wants to surveil and police what she calls “malign creativity.” We’re constantly being propagandized. Rather than tackling serious questions and supporting meaningful debate, our reigning information ecosystem funnels us into one of two self-contained siloes — Team Red versus Team Blue — whose primary justification for existing is that they are not The Horrible Other.

Rethinking the Horseshoe

Still, as noted, there are many — and often much better — political analyses, opinions, and positions out there. That said, as bad as our dominant political discourse may be, it remains true that it could be much worse. In principle, thinking outside of the box is good. But in practice, it’s far from foolproof. Even on a conceptual level, trying to navigate the further reaches of our current political landscape can be a dicey endeavor.

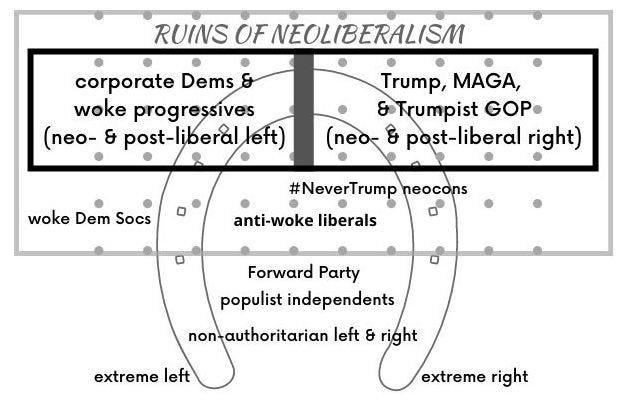

With that caveat in mind, my best sense of the current state of American political discourse looks something like this:

Here, the light grey box at the top with the dots inside it (labeled “ruins of neoliberalism”) represents the shift from the shared liberal space of the “old” postwar horseshoe (see first graphic, above) to the newer neoliberal order (described by points #1-7, above). In the “old” model, the core dynamics of American politics were widely presumed to be benign and constructive. (The extent to which this perception was right or wrong is a separate issue I won’t go into here.) In the “new” model, however, the equivalent space is widely seen as sick and destructive.

Overall, the “Team Red” vs. “Team Blue” narrative dominates the entire political and cultural landscape. Both on the right and the left, these dominant positions include strong neoliberal elements (primarily the party establishments) and various post-liberal factions (primarily wokeism on the left, and anti-democratic authoritarians and “burn it all down” nihilists on the right).

In both cases, these neo- and post-liberal elements have a symbiotic relationship in which each enables the other to amass power. The passionate convictions of wokeism, for example, help legitimate the moral vacuousness of the corporate Dems — who, in turn, reward the wokesters with institutional power. Conversely, Trump’s bombast channels the energy of populist rage, white resentment, anti-establishment fervor, and/or hatred of the liberal elite into an otherwise moribund Republican Party — which, in turn, gets the tax cuts and conservative court appointments they’ve always wanted.

Other, smaller political movements noted inside the grey box (“woke Democratic Socialists,” etc.) are essentially working within the same parameters as the dominant Red vs. Blue discourse. While distinct entities with more and less worthwhile perspectives to offer, they’re not really “thinking outside of the box.”

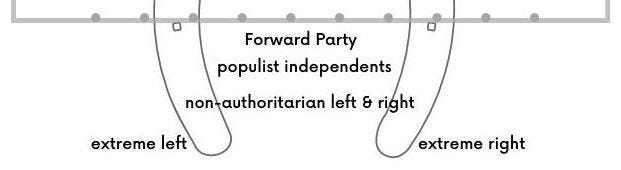

In contrast, the bottom portion of the graphic represents more truly “outside the box” political thinking, organizations, and movements — which, again, doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re better than the dominant paradigm. They are, however, different. And, in a political culture that’s characterized by so much rigid narrative control, that, in and of itself, is worth noting.

Political Heterodoxy & Creative Freedom

The lower center of the horseshoe — that is, the space outside the box of neoliberalism, yet untethered from the extremes of the left or right — is, in my opinion, the most promising place to be.

It’s worth emphasizing that this is not the so-called “political center.” On the contrary, in this conceptual mapping, the “center” would be the thick, dark grey line that separates the corporate Dems and wokesters from the Trumpers and GOP — a place that is, essentially, nowhere.

Even though it’s positioned between the far left and the far right, this lower center of the horseshoe space is better characterized as “politically heterodox” than “centrist.” It’s outside, rather than in the middle of the dominant political culture. It attracts people who are willing to break the cardinal rule of the dominant Red vs. Blue paradigm: That is, being open to ideas, conversations, and debates that cross the presumptive right/left divide. The reigning narrative, which insists that to step outside your prescribed box is to slide down the slippery slope to perdition, is either explicitly or tacitly rejected. Rather than being demonized, “outside the box” thinking is respected, both for its potential value and because it’s indispensable for creativity and freedom.

Examples listed on the graphic above include:

Andrew Yang’s latest venture, the Forward Party, which is trying to break the dominant two-party “duopoly,” open up the American political system, and spearhead meaningful pro-democratic reforms.

“Populist independents,” as exemplified by the independent news show Breaking Points, who may come from the left or the right, but commonly reject neoliberalism, authoritarianism, the dominant narrative, and two-party control.

The “non-authoritarian left,” which is committed to the traditional socialist goals of empowering ordinary people and creating a more equal society, but rejects the centralized authoritarianism of the far left (examples here, here, and here).

The “non-authoritarian right,” which critiques the ways in which liberal modernity has undermined family, faith, and community, but advocates for their revival in an updated, “reactionary feminist” form (examples here, here, and here).

Not listed but implicitly included in this space are also the many independent journalists, writers, and podcasters whose work crosses political boundaries and champions creative freedom (examples here, here, here, and here).

In this space of horseshoe convergence between the right and the left, it’s possible to think creatively while rejecting the anti-democratic authoritarianism of the extremes. In and of itself, this is a positive personal practice, regardless of whether it ever accomplishes anything politically. It’s also a good interpersonal practice, as it orients us towards trying to connect with people across differences, rather than automatically putting anyone who doesn’t parrot the exact same party line as our peers into the “enemy” box.

Best case scenario, it may even turn out to be an important social practice, if it somehow succeeds in leveraging us out of the downward spiral we seem to be collectively trapped in. That, of course, very much remains to be seen. But at least within the safety of our own minds — and more publicly, if and when our personal circumstances permit it — we can break out of the boxes imposed by the dominant culture and experience more vibrancy, possibility, creativity, and freedom.

Very good piece. I saw a reference to your writing on Developmental Politics.

I am 1/3 of the way through the book I would have written about our system had I pursued a PhD beyond my BA in Political Science 50 years ago. Much of our issues are structural, and the result of elite failure. https://americanexception.com/book/

Several of the thinkers who you mention are critics of the excesses of wokism. As part of those excesses, people are denounced and charged with transgressions without any finding of facts or intent, or application of a moral basis. That’s vigilantism, and liberal discourse is a casualty. The means of this, as you say, are “scaring doubters, resisters, and critics who otherwise considered themselves ‘on the left’ into silence, submission, and/or ostrich-like denial. (One reason, obviously, why this is a bad deal is that targeted individuals may become generally alienated from progressive political currents, or at least participation in those.)

Jacobinism is one extreme approach; another would be a kind of counter-Jacobinism that whitewashes or ignores inequities that have to do with the forms and results of oppression. Those thinkers who are politically heterodox aren’t off the hook, of course, from addressing issues of systemic injustice. (Yang has a refreshing approach in that his program clearly seeks to solve the roots of division in American society.) One of the demands of the wokesters – a valid one, I think – is that anyone who has a forum has a responsibility in these times to speak to matters of social justice. Some of these matters involve racism or sexism, and the wokesters don’t want people to avoid the conversations on these, whatever their job or field may be.