When I launched “Liberal Confessions” in late 2021, I described myself as a “progressive liberal apostate.” As a starting point, this characterization was and remains true. Since that time, however, I’ve come to the conclusion that what many people call “wokeism” can be more precisely described as “post-liberal progressivism.” Consequently, the categories of “progressive” and “liberal” have become much more sharply separated in my mind.

This used to not be the case. Back in the late 20th century, when I was proud to be a “card-carrying member of the ACLU" (I now belong to FIRE instead), I saw the terms “liberal” and “progressive” as more or less synonymous in the American context. Today, however, I believe that it makes sense, both descriptively and analytically, to parse them as distinct categories. This isn’t because I think that my old understanding of them was wrong: In the context of its time, it was essentially correct. But that time — as we would all do well to recognize by now — has passed.

Since the late 2010s, it’s become clear that the nexus of political and cultural commitments, beliefs, practices, and institutions that predominantly represents “progressivism” in the U.S. no longer includes any serious allegiance to liberal values. This isn’t to say that today’s progressives flatly reject basic principles of the broadly defined liberal tradition, such as freedom of speech, the rule of law, and limited government. They don’t — at least not explicitly, consistently, and out loud.

What’s true, however, is that such quintessentially liberal commitments no longer command any true loyalty, animate any serious inquiry, or arouse any heartfelt passion on the part of the progressive left. Whether it’s openly stated or — as is most often the case — not, the dominant form of American progressivism has effectively become post-liberal. Consequently, it makes sense for former “progressive liberals” like myself who continue to be committed to certain core liberal values to disassociate from the “progressive” label entirely.

The Post-Liberal Power Structure

The center of gravity for the progressive left has shifted. Throughout the long 20th century, it was driven by a socially equalitarian form of left-liberalism rooted in the New Deal and Great Society, and the Civil Rights and 2nd-wave feminist movements. Today, in contrast, its most passionate commitments are to “dismantling the gender binary” and promoting Robin DiAngelo-style “anti-racism.” Both in theory and practice, these racial and gender politics (as well as their many intersectional spinoffs) not only have no investment in the foundational liberal values that animated their historical precursors, but are in fact quite hostile to them.

Institutionally, the “genderqueer” and “anti-racist” goals of today’s progressivism translate into a drive to enculturate as many people as possible into this new ethos through such means as Title IX bureaucracies in the educational system, DEI trainings in the workplace, activist campaigns in the news media, and coordinated efforts to control salient information on the Internet. Of course, the carrots offered to get people on board with the program are regularly backed up by sticks. Everyone, we’re reassured, will be supported in the never-ending process of “doing the work” needed to “educate” themselves properly. But of course, they’ll also be “held accountable” if they fail to live up to expectations (or perhaps even if they do, but are unfortunate enough to encounter some powerfully positioned enemies).

The fact that post-liberal progressive culture is backed up by a growing set of organizational power structures is never acknowledged in woke or woke-friendly circles, however. Consequently, the question of precisely what the governing rules of these new systems are — not to mention, what they ideally should be and why — is never publicly raised, let alone discussed. Instead, a sprawling system of byzantine bureaucracies peppered with activist professionals has developed. And it holds a lot of power over a lot of people. Yet, it has no public transparency. To the average person and even most highly educated professionals, the sprawling scope of the growing PLP institutional infrastructure is not only opaque but invisible.

Of course, within the context of Blue State culture, it’s easy to obscure and legitimate this system by pumping up the smokescreen claim that there’s no “there there” beyond a virtuous promotion of the same “equal rights” vision that animated old-school progressives back in the day. In fact, however, both the culture and structure of this new form of progressivism are profoundly post-liberal. They do not represent an extension of that 20th-century tradition, but a dismantling of it.

After all, a foundational part of the traditional liberal vision is that laws, rules, and policies should be publicly legible and transparent. Such visibility is necessary if the rules we’re subject to are to remain open to public debate and, as appropriate, democratic reform. It also protects individual rights, as citizens can see where lines are drawn and understand the consequences of crossing them. These protections are also, of course, core liberal commitments.

The fact that such liberal ideals have never even come close to being fully achieved in practice doesn’t mean that they’re necessarily bad aims to have. A commitment to the rule of law, for example, provides a standard against which positive legal change can be — and often has been — successfully leveraged in practice. (Consider the raison d’etre for funding public defenders or passing the Freedom of Information Act.) The fact that such policies don’t consistently work out as well as we’d like doesn’t mean that getting rid of the norms that undergird them will necessarily make anything better. On the contrary, a society that accepts that there are many new rules to follow and rule-makers to enforce them, but refuses to consider the foundationally liberal democratic contention that citizens have a right to understand, discuss, and critique them is much worse off than one that maintains that norm, even if it’s often in the breach.

The Successor Ideology Has Succeeded

Unfortunately, what Wesley Yang so memorably called the “successor ideology” has clearly succeeded. Back when he first coined this term in 2019, it generated a good deal of attention from those of us who were aware that some major political and cultural shift was afoot, but couldn’t yet quite wrap our heads around the fact that the left-liberalism we’d long identified with was truly being demolished and replaced.

Pithily, Yang went on to characterize this new ideology as “a kind of authoritarian Utopianism that masquerades as liberal humanism while usurping it from within.”

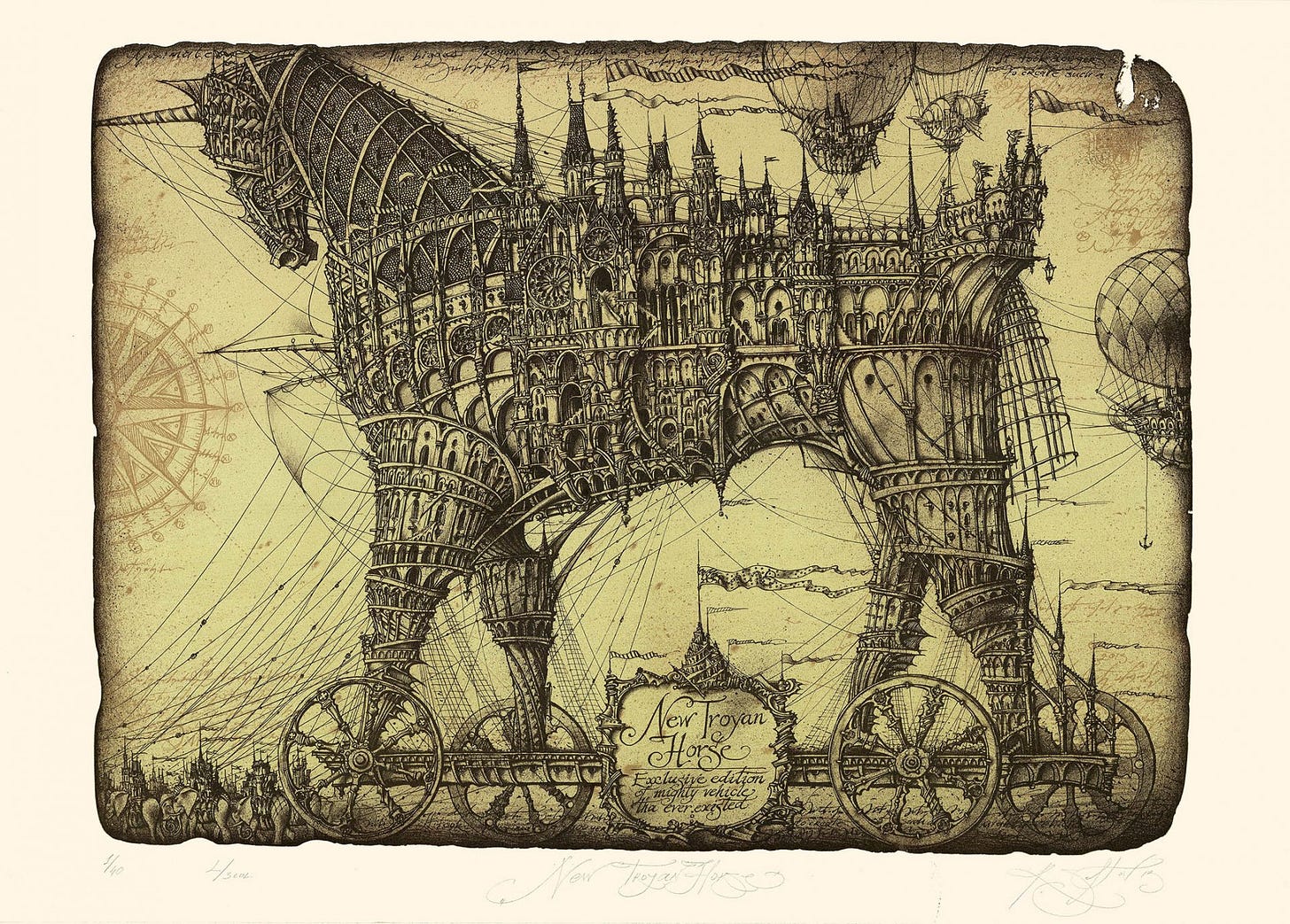

Four years ago, Yang’s succinct Tweet captured the Trojan Horse quality of this seismic political and cultural shift quite well. As the successor ideology — or wokeism, or post-liberal progressivism, or whatever you want to call it — moved into the citadels of America’s premier cultural, educational, media, tech, nonprofit, and Democratic Party-affiliated political institutions, no one announced it as an incipient takeover. On the contrary, the whole question of whether any sort of break with the liberal humanist tradition was in fact occurring was immediately thrown into the cultural and conceptual trash bin of “right-wing reaction” (and later, “disinformation”). Yet, that’s precisely what was happening.

It took me some time to realize this. But eventually, I saw it clearly. And after that, one logical consequence was to separate the categories of “progressive” and “liberal” much more clearly in my mind.

Again, as I’m conceptualizing it, today’s progressives are effectively post-liberal. This means that while they’re not explicitly hostile to liberalism, it’s not even a remote priority. Other political, social, cultural, and personal commitments, which are rooted in very different philosophies such as postmodernism, queer theory, critical race theory, and 3rd and 4th wave feminism, are infinitely more important.

This isn’t to say that most of today’s self-styled progressives are truly invested in such ideologies. Some are, but most aren’t. Regardless, they constitute today’s progressive Zeitgeist. And this new post-liberal progressivism and the old progressive liberalism are different enough that to call oneself a “progressive liberal” no longer makes sense. That particular political identity was part of a 20th-century cultural formation whose time — like it or not — has passed.

Particularly for those of us who are old enough to have been socialized into it, this loss comes as a shock. Despite the enormous problems of the mid-to-late 20th century, progressive liberals of that era had a sense of confident optimism about the future. Particularly during the 1990s, when the Berlin Wall came down, the U.S. economy was booming, and the Internet was just entering the public sphere, it seemed that the many troubling social, political, and economic issues we faced could be tackled. While this faith was subsequently shaken by 9/11, the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and the 2008 financial crisis, Barack Obama burst onto the national political scene at exactly the right time to promise to restore it.

That isn’t, however, what happened. And it’s past time to recognize that not only has the world fundamentally changed, but that there was some serious myopia in the old-school progressive liberal vision. There is nothing shameful about this admission; it would be at least equally true for any other political perspective, whether then or now. It’s simply easier to see certain things more clearly in hindsight. In order to do so, however, you have to look.

Today’s progressives don’t want to take a serious look back at their roots and try to parse through what went right, what went wrong, what’s worth holding onto, and what deserves to be discarded. Instead, they’re intent on jumping with both feet into the fundamentally different (yet confusingly camouflaged as the same) post-liberal progressivism paradigm — or, as is more often the case with people of my generation, simply pretending that nothing fundamental has really changed. But whether we like it or not, it most certainly has.

And So — Then What?

Where does that leave those of us who still nonetheless retain a certain allegiance to at least some core aspects of this now-defunct old-school progressive liberal paradigm? Personally, I’d say that cultivating acceptance for the fact that times have indeed changed and giving ourselves full permission to change along with them is a good place to start.

That sounds simple. But it’s not. Both are difficult feats, particularly for people who feel some sense of attachment and loyalty to this once widespread political and cultural perspective. Changing your social identity and worldview is hard. And this is particularly true when there is substantial social pressure not to do so.

This difficulty, however, can be eased by practicing a determined sense of open-minded curiosity. Connecting with the many positive political and cultural developments that are currently happening outside the bounds of the stultifyingly oppressive “Blue vs. Red” framework we’re supposed to stay in is not only helpful but — at least, over time — energizing and uplifting. Initially, it may be little more than disillusioning and disturbing. But eventually, that will change.

Even though there’s a concerted effort on the part of some quite powerful forces to keep us locked into our respective Blue or Red boxes, there are a lot of people out there who are refusing to play that game. Refreshingly, such “heterodox” thinkers come from a wide diversity of backgrounds, identities, and traditions. And while they (or should I say “we”?) don’t yet form any sort of coherent cultural or political network, there’s no doubt that our numbers are growing.

You’d never know it, though, if you only listened to the mainstream media. But if you’re willing to go beyond where “they” say you should, there’s actually quite a lot of interesting and potentially even valuable political discussion and cultural inquiry happening today, both in the U.S. and internationally. You just have to go off-road to find it. (Of course, since you’re reading this article on Substack, one of the premier platforms for supporting such work, you’ve already done that.) True, this new terrain is more uneven, less predictable, sometimes challenging, and occasionally treacherous than what you’ll find if you follow the rigidly predictable Red/Blue roadmap. But it’s also infinitely more interesting, original, honest, and insightful — and even, at times, brilliant and inspiring.

Personally, I’ve become more and more impressed by the quality of the political analysis and cultural discussion available today. There are a lot of independent journalists, writers, podcasters, and videographers, and many of them are quite good. In fact, there’s so much worthwhile content out there, it’s hard to prioritize what to spend time on. All things considered, though, that’s not a bad problem to have. Certainly, it’s infinitely better than staying locked in some mind-numbing box in which you’re being covertly trained to censor your own thoughts before you even have them.

But what good, one may ask, will any of this do in the bigger picture? Are any of these small-fry podcasters, Substackers, and other independent voices ever really going to add up to anything capable of countering The Narratives favored by The Powers That Be? Perhaps not. But the fact remains that taking advantage of the opportunity to listen to diverse voices, encounter new ideas, and exercise your own innate freedom of thought, conscience, and expression is valuable in and of itself. This doesn’t mean that everyone should devote themselves to being some sort of part-time political analyst. But it does mean that we’d all be better off ditching the dominant Blue vs. Red narrative and connecting with positively-minded others who’re doing the same.

Blow up your TV throw away your paper

Go to the country, build you a home

Plant a little garden, eat a lot of peaches

Try an find Jesus on your own

— John Prine, “Spanish Pipedream” (1971)

Thanks everyone for the great comments. I have read everything and want to reply but have just been too busy. I will definitely try to do so sooner rather than later, though. In the meantime, thanks again for reading and sharing your thoughts.

Hi, Carol.

There are many insights that you share in both this piece ("Why I'm No Longer a Progressive" and the one on "Toxic Feminity" (both are oh so excellent; I don't even know where to begin!) that seem to align well with the insights in these two essays from the co-founders of Protopia Labs (an organization dedicated to depolarization). They both use some similar language though with slightly different nuances. I think you'd really like their work, and I *know* they would appreciate yours. (Going to post this comment on both of your essays, if that's okay).

"Why We Need to Talk about Post-Liberalism" by Micha Narberhaus

https://michanarberhaus.substack.com/p/why-we-need-to-talk-about-post-liberalism

"Pride of the Elites: Political Correctness, Identity Politics and Class War:

How Elite Overproduction drives culture wars, and how to move beyond it" by Alexander Beiner

https://beiner.substack.com/p/pride-of-the-elites-political-correctness